Report: Whose history do we choose to remember? About public spaces, statues and cultural choices.

On the thirteenth of November, PAF brought together interdisciplinary curators and speakers to discuss how monuments and public spaces continue to reflect narrow, often gendered and colonial narratives, and how these can be reimagined. The curators consisted of Nele Maes, urbanist and researcher at Erasmushogeschool Brussels and Titaantjes Collectief, Camille Van Peteghem, a legal researcher at KU Leuven, and Fien Van Rosendaal, a cultural sociologist. Among the speakers were Stephanie Collingwoode Williams, an anthropologist who is also part of the Congolese-Belgian filmmakers collective Faire-Part, and Léone Drapeaud, an architect and co-founder of the collective Traumnovelle. The panel discussion was moderated by Nele Maes.

Text: Dilara Kabak

Photos: Tatjana Huong Henderieckx

Listen to the full audio recording of the discussion evening.

The curators and speakers exchanged ideas and even invited the public to participate after the panel discussion. Camille started by sharing her own personal experiences of gender inequality in legal academia, where she was early on surrounded by portraits and statues of old, white men. She realized how these statues don’t only immortalize white men, but always individual leaders, as if they made it entirely on their own. As if they didn’t stand on the shoulders of giants. Camille raises the question: what about community?

Who Gets Remembered? Rewriting Collective Memory

We continued the conversation with Camille Van Peteghem, who spoke about taking part in a commemoration event organized by Lean In Leuven Law that celebrated the 100th anniversary of female students in her faculty. One detail that stood out was her consistent use of the first-person plural “we”. Even after the event, when congratulating her on her powerful talk, she simply replied, “we did that,” emphasizing the collective effort.

For the commemoration project, Camille researched the faculty’s first female student, Germaine Cox. To honor her, the team of Lean In from the faculty worked on a mosaic of Germaine that also included all the female students and technical staff. The mosaic not only paid tribute to Germaine, but also to the generations of women who followed her, the ones who stood on the shoulders of female giants.

Some might argue that this is merely a symbolic gesture, but Camille highlights that symbolism matters. Statues, monuments, street names. They tell stories about what we deem important enough to remember. This raises key questions about how such decisions are made: Who is chosen to represent our shared history? How many women, people of color, and queer people are represented?

The issue is not only about numbers but also about the nature of representation. The statue of Molly Malone in Dublin, for example, illustrates how its accessibility to the public has come at a cost: her breasts have been touched so frequently by passersby that the bronze around her bosom has changed color.

In contrast, statues of white men are typically elevated on pedestals, often depicted on horseback. This is not accidental; the elevation symbolizes hierarchy and power. Moreover, while statues of white men tend to portray individual heroic figures, female statues are more often mythological or allegorical, such as the Statue of Liberty.

Once again, symbolism matters. Yet, Camille argues that when symbols become so familiar that we stop noticing them, they become dangerous. What we don’t see, we can’t resist. So, how do we resist? Analysis alone isn’t enough; we need to act. We need to rewrite these stories in a more inclusive way.

Reimagining Monuments in Practice

We then turn to Fien Van Rosendaal, who introduces a framework for the conversation, based on insights shared by Léone Drapeaud. The first part focuses on challenging the story by recognizing the issue: naming the problem, taking it apart, brick by brick. We dethrone the white men from their (high) horse. The second part is about changing the story. Here, we remove the pedestal and replace it with something new. We move away from fixed figures and create spaces for new, shared narratives.

So how does this work in practice? Stephanie Collingwoode Williams and Léone Drapeaud offer concrete examples of how their collectives rewrite these stories. As part of Traumnovelle, Léone worked on “The Grand Opening”, an installation that temporarily transformed a colonial monument. Rather than hiding or erasing the colonial past, the monument was reshaped into a space to be used for performances and discussions about the colonial past. Léone points out how removing the monument would also remove the narrative. And if we remove the narrative, we can’t question it.

Opening Space Through Friction

Stephanie argues that a colonial monument cannot simply be removed without first creating space for a meaningful public conversation about that removal. As an example, she refers to the wooden pedestal that SOKL, an initiative of Collectif Faire-part, put next to a statue of King Leopold II. By removing the king, they created a space that invited other stories: artists were encouraged to use the pedestal to tell their own. The project was participatory rather than fixed, in contrast to the permanence of traditional statues. Even the weather contributed to its impermanence; through rain and wind, the wooden pedestal continually changed.

Because the installation stood in public space, anyone could access and interact with it. Stephanie emphasizes that this accessibility also introduced risks: people who view the colonial past positively could just as easily participate. She argues that even spaces designed to be safe and inclusive can still lead to discomfort or harm, and that many people are not yet ready for difficult conversations or conflict.

Léone adds to this discussion introducing a 2018 Traumnovelle project for the Belgian Pavilion at the Biennale di Venezia. The installation created conflict and friction: doors were too low; steps were slightly too high. Despite this, children climbed the structure, and visitors even started dancing. For Léone, such moments show that when we remain open to conflict, we allow new forms of collective engagement to emerge.

Imagining New Forms of Collective Presence

Nele Maes brings us to the next question: What kinds of symbols do we still need? After addressing gender inequality and the colonial past in public spaces, Stephanie draws attention to economic inequality. Instead of symbols, she advocates for concrete action: less anti-homeless architecture, free public toilets, the use of empty buildings as shelters, bus stops that offer protection from the rain, and more third spaces where people can come together.

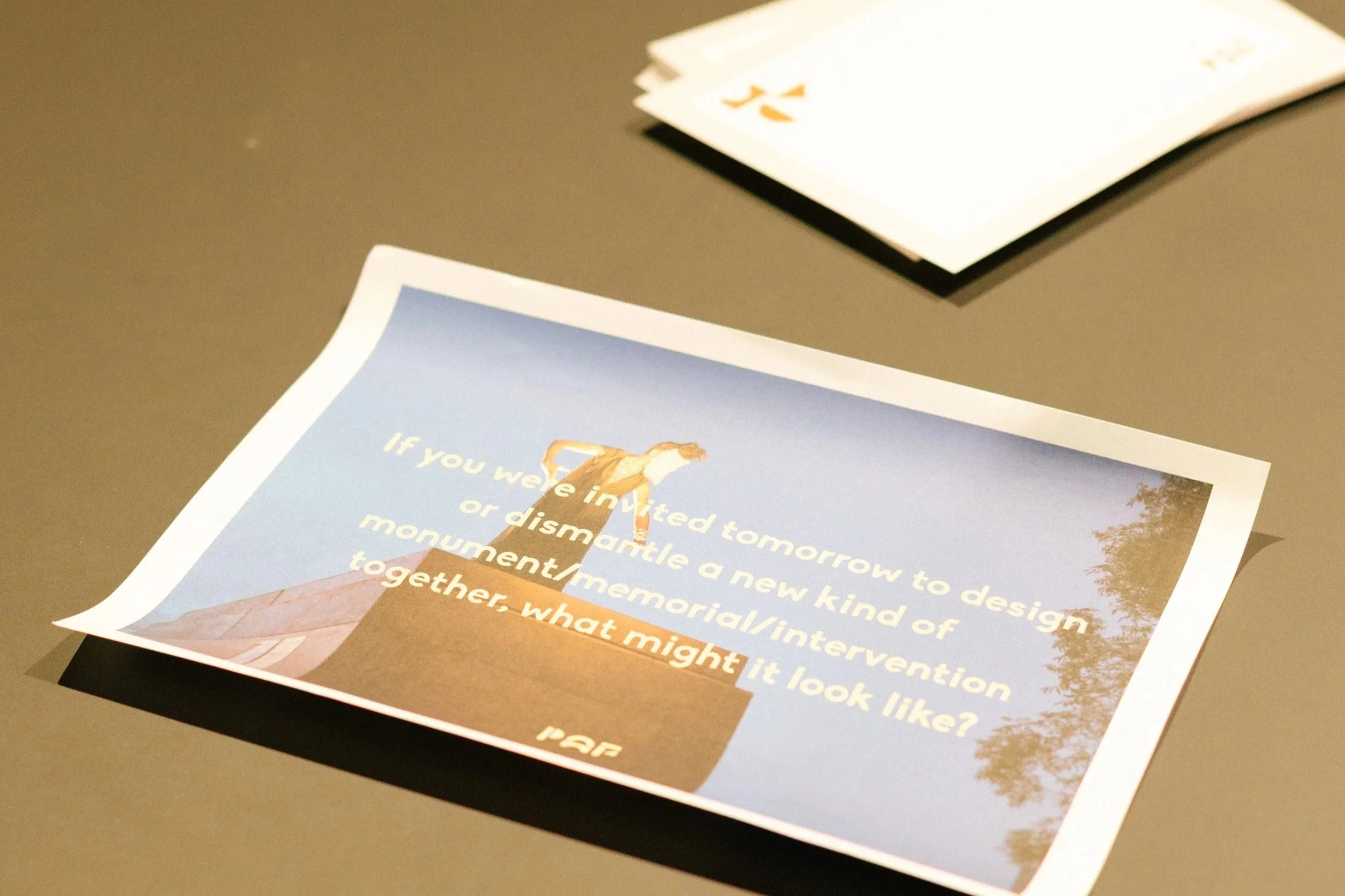

When the panel discussion comes to an end, Fien reminds the audience that public spaces are continually reshaped through dialogue and participation. She then invites everyone to engage through dialogue in smaller groups. We're all asked to reflect on the question: If you were invited to design a new kind of monument or memorial, what might it look like?

Someone mentioned the two-kilometer-long iftar table in Antwerp, a participatory initiative where people not only share food, but stories. Another person wondered whether trees and plants can give public space a new context. As an example, they talked about the statue of Leopold II in Halle, which became overgrown with ivy. “Let nature take over”, he explained.

What about you?

How would you imagine it?